On Oct. 17, 1989—36 years ago today—an earthquake measuring 7.1 on the Richter scale struck the San Francisco Bay area. By the time the 15-second quake ended, it was on its way to being one of the most lethal earthquakes in U.S. history. About 100 people died, hundreds were injured and thousands left homeless. Damage was in the billions.

The quake destroyed buildings and bridges and tore up roads, including a mile-long stretch of the elevated portion of Interstate 880, just behind the Oakland Distribution Center. The roadway buckled and concrete beams crumbled, causing cars on the top level to plunge downward and those on the bottom to be buried under tons of concrete and steel.

The Oakland DC felt the quake strongly. The manager’s office pitched wildly. Ceiling tiles fell. Windows broke. Security technicians and managers searched through the more than 1 million-square-foot complex with flashlights, digging through the rubble in the dark, calling out for associates. Others checked the parking lots for cars that could be matched to anyone who might still be inside.

The buildings had moved a full foot to one side and back again, derailing many of the 20-by-15-foot sliding doors on the sides of the building. Because the doors couldn’t be closed, the DC couldn’t be secured. Safety and security technicians volunteered to stay through the night and patrol the area.

The DC’s night shift experienced the quake firsthand. Four minutes before the quake hit, associates had left their work stations to go on break. If they had been in the compound when the quake struck, many would have died. All were quickly released to check on their families at home.

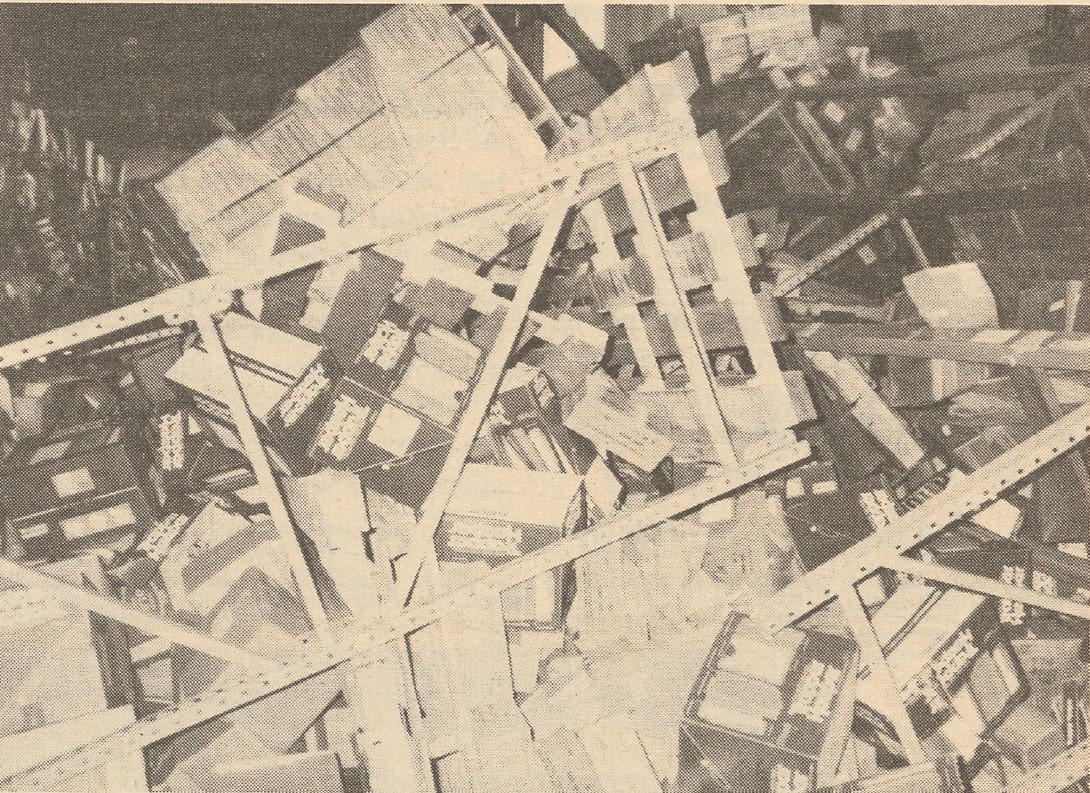

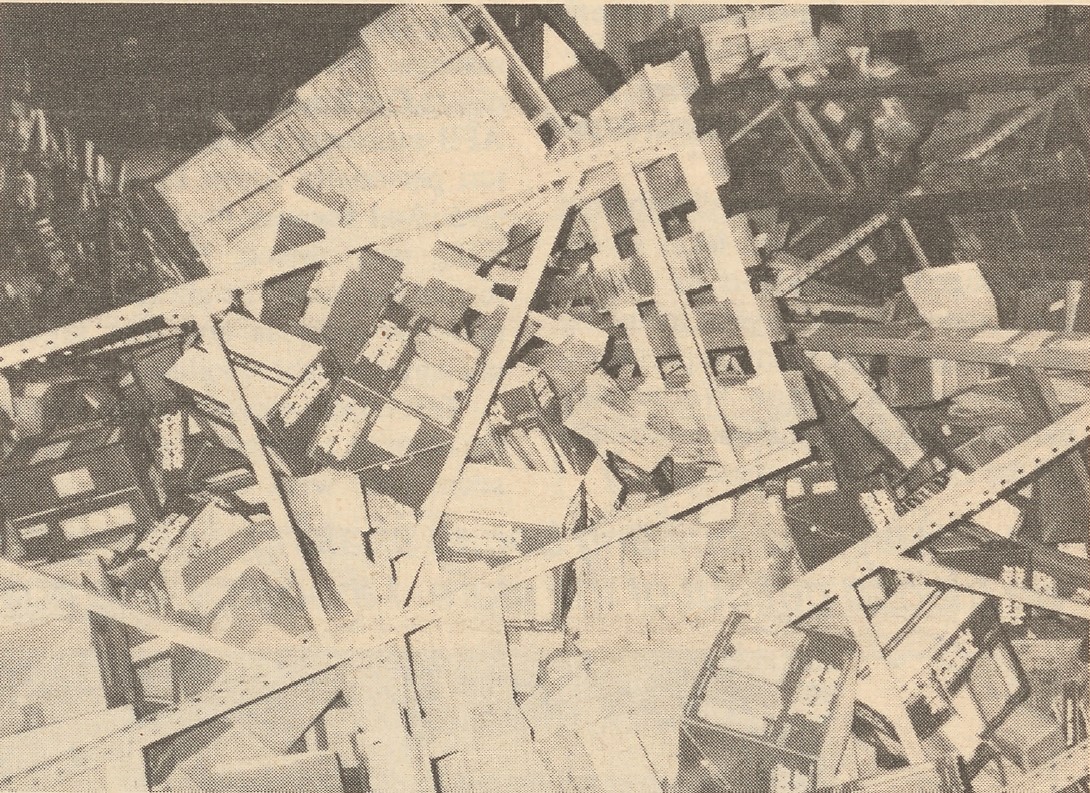

Minutes before the 1989 Bay Area earthquake, Oakland Distribution Center teammates had been working in these aisles. They took a break at 5 p.m. and left the area. The earthquake hit at 5:04 p.m.

Entire sections of racks had collapsed. Sections as large as 30,000 square feet had fallen like dominoes, interlaced with broken light fixtures and water lines. Even the racks that hadn’t collapsed were so damaged that all merchandise had to be removed before normal operations could resume.

Many associates returned quickly to work on getting the DC operating again. To help families living on Oakland Army Base, the DC donated bottled water and moved basic items into the small Exchange facility on the post.

Only one associate injury was recorded: While trying to help a 7-year-old boy who was so stunned that he could not move from his huddled position near a cash register, a supervisor slipped and fell on the floor. Several associates lost family members, however, in the collapse of highway I-880.

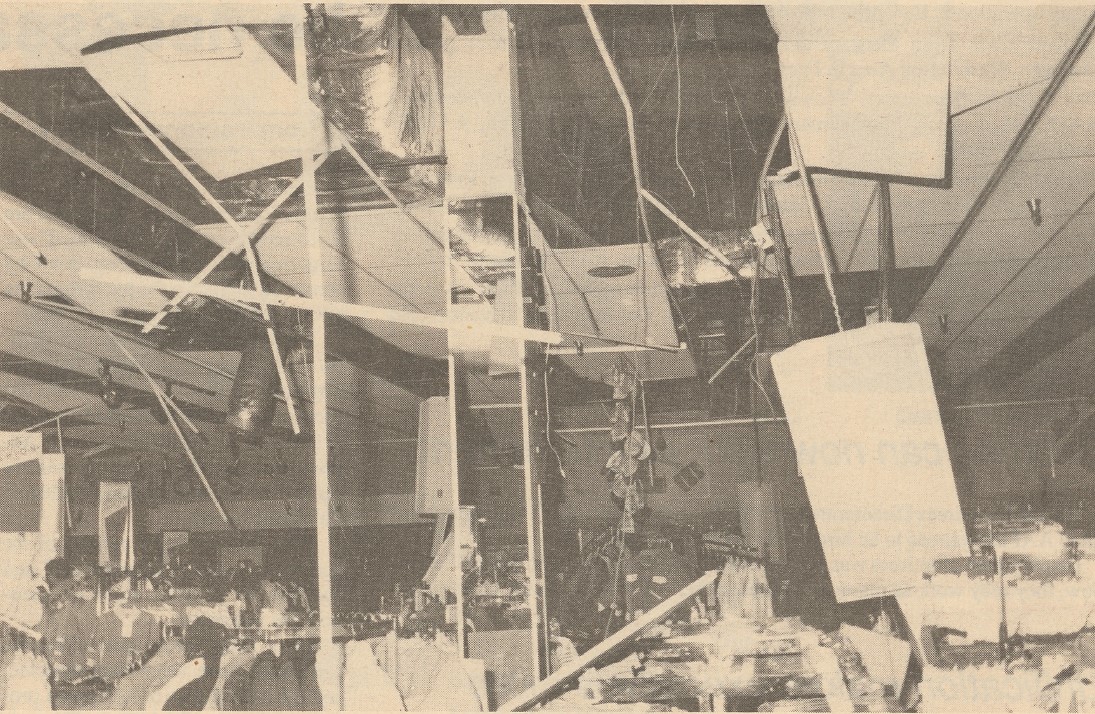

At the Presidio of San Francisco Exchange, facilities were littered with broken glass. Merchandise was thrown from shelves. Ceiling tiles fell and entire rows of lighting fixtures dangled precariously from exposed electrical wires hanging from what was left of the ceiling. At the Four Seasons store, gallons of paint had burst open when they were slammed to the floor. A car had partially slipped off a lift rack while being serviced at the service station. The Exchange facilities suffered more than $150,000 in damage. Despite the damage, the Presidio of San Francisco PX donated bedding and portable lighting to the City of San Francisco.

Earthquake damage at the Presidio of San Francisco Exchange in 1989. (U.S. Army photo)

At the Fort Ord Exchange, roughly 115 miles southeast of San Francisco, pictures fell off the walls of the food manager’s office. As she opened her office door to flee, she saw the entire stairway and porch sway back and forth. The power failed. But by the next day, the PX was back in business. It operated in darkness, allowing no more than five customers in at a time. Flashlights became the primary means of light.

The Fort Hunter Liggett Exchange manager sent merchandise to Fort Ord, 86 miles away. The Castle AFB Exchange manager personally drove supplies to Fort Ord.

The Exchange Post reported on, but did not identify, one Shoppette that used cigar boxes as cash registers. Associates provided illumination by shining their car headlights into the store.

The Oakland DC recovered enough to continue operating through the early 21st century. The West Coast DC—which opened in July 2001 at the Sharpe Army Depot in Lathrop, Calif., 60 miles east of San Francisco—took its place.

The quake was not the first 1989 disaster that affected Exchange facilities. Less than a month earlier, on Sept. 20 and 21, Hurricane Hugo ravaged the Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, and Charleston AFB, South Carolina, causing an estimated $656,000 in damage to Exchange facilities at St. Croix, Puerto Rico, and Charleston and Shaw AFBs in South Carolina. As in San Francisco, some facilities were operated using flashlights and hand-held calculators.

Sources: “One Hundred Years of Service: A History of the Army and Air Force Exchange Service”; Exchange Post archives.

Leave a Reply